|

|

|

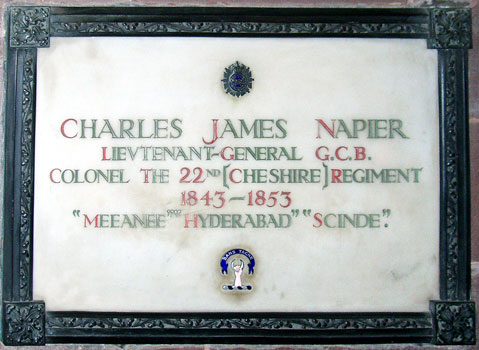

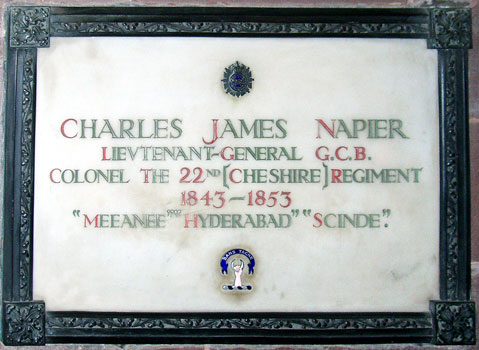

| Statue in Trafalgar Square, Aug 2006 | Monument in Chester Cathedral |

Sir Charles Napier had a remarkable military career, starting with the Napoleonic Wars and continuing into the middle of the 19th century with a variety of overseas campaigns and in particular in India. The monument to Napier in Trafalgar Square shows him bearing a scroll, symbolic of the administration of Sind and in his right hand is a sword held to his breast. On the pedestal is the inscription "Charles James Napier, General, born MDCCLXXXII; died MDCCCCLIII. Erected by public subscription from all classes, civil and military, the most numerous subscribers being private soldiers".

|

|

|

| Statue in Trafalgar Square, Aug 2006 | Monument in Chester Cathedral |

The Napiers were a Scottish family and one of the members in the 16th century was the mathematician who invented Naperian logarithms. In the 18th century the heiress of the family married one of the Scott family of Thirlstane Castle and her son, Francis, took the name of Napier to succeed as the fifth Lord Napier. He married twice and left several children. His son by his first wife gave succession to the barony but by his second wife he had a son George who became a Colonel. According to the book by J. G. Edgar (see sources) George married Lady Sarah Lennox, daughter of the second Duke of Richmond and their eldest son was Charles James Napier. The Dictionary of National Biography states that Charles was the eldest of four sons of Colonel the Honourable George Napier and his second wife, Lady Sarah Bunbury.

Charles Napier was born in Whitehall on 10 August 1782. In 1785 the family moved to Celbridge near Dublin. Charles began his military career as an ensign in the 33rd Regiment in January 1794 and on the 8 May was promoted to lieutenant in the 89th regiment at Netley Camp. His father was the assistant quartermaster-general. When the regiment sailed for Ostend, Charles was moved to the 4th regiment and sent to a grammar school in Celbridge. In 1799, Charles Napier became aide-de-camp to Sir James Duff, who commanded the Limerick District. Over the next few years he was based variously in England and Ireland and at one stage was aide-de-camp to his cousin, General Henry Edward Fox, commander in chief of Ireland. Another cousin was the Whig politician, Charles James Fox.

In December 1803, Napier, still only 21, became a captain in the staff corps. This was a group raised to assist the royal engineers and quartermaster general. He was based in England at Chelmsford and Chatham. In October 1804 Charles' father died but his widow and daughters received a pension from William Pitt, the then Prime Minister. In 1805, Charles was involved with his corps in the construction of the Military Canal at Hythe under the command of Sir John Moore, who was training the 43rd, 52nd and rifle regiments. Two of Charles' brothers were there - William in the 43rd and George in the 52nd regiment.

There was a change of government in May of 1806 and Fox became Prime Minister. Napier was promoted to Major in a Cape Colonial Corps but subsequently moved to the 50th regiment at Bognor in Sussex. This regiment was deployed in Guernsey, Deal, Hythe and Ashford in Kent during the following two years. In 1808 Charles was ordered to join the 1st Battalion of the 50th regiment at Lisbon and became the commander of the battalion. Sir John Moore placed Napier's battalion in Lord William Bentinck's brigade for the next phase of the Peninsula War. On 16 January 1809, at the battle of Coruna, Napier led his men and was wounded five times. He sustained a broken leg from a musket ball, a sabre cut to the head, a bayonet wound in the back, broken ribs from gunshot and injuries from being struck by the butt of a musket. Napier was taken prisoner and was initially reported as dead. However, he was saved by a French drummer and taken to Marshal Soult's quarters where his injuries were treated. Later, Marshal Ney, freed him on condition that he did not fight again until exchanged for a French prisoner. This took place in January 1810.

Napier then obtained permission for leave of absence from his regiment and joined the Light Brigade as a volunteer. The brigade was then in Portugal and Napier's two brothers were in it. He had two horses shot from under him at the battle on the river Coa on 24 July 1810. Napier was then attached to Wellington's staff and at the battle of Busaco on 27 September 1810 he was shot in the face, which broke his jaw and injured an eye. He was sent back to Lisbon and on 6 March 1811 he set out to rejoin his regiment. On the 13th he rode 90 miles in a day on one horse and rejoined the army. The Light Division was in the vanguard and in constant contact with the French rearguard under Marshal Ney. On the 14th, Napier met his brothers William and George, both wounded and being carried to the rear. Charles Napier was involved in the battle of Fuentes d'Onoro on 5 May 1811 and the second siege of Badajos.

On 27 June 1811, Napier was promoted from Major to become Lieutenant Colonel of the 102nd regiment which had just returned to Guernsey from Botany Bay. Lord Liverpool then granted him the sinecure of governor of the Virgin Islands, which did not require residence, as a compensation for his wounds, a post he resigned soon afterwards when pensions for wounds were introduced. In July 1812, after a few months in Guernsey, Napier sailed with his regiment to Bermuda. The following May, he was given command of a brigade to take part in a campaign of the War of 1812 against the United States under Sir Thomas Sydney Beckwith. The brigade went to Hamton Roads and seized Craney Island and the town of Little Hampton. Later that year, Napier was involved in minor actions on the coast of Carolina and then went with his regiment to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Napier then transferred from the 102nd back to the 50th regiment but on his return to England in September 1813 the war was over. He was placed on reserve on half pay in December 1814 and so he joined the military college at Farnham with his brother William. In March 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and regathered his forces. Napier went as a volunteer and took part in the storm of Cambrai and the entry of Paris. He received a gold medal for his services at Coruna, and a silver war medal with two clasps for Busaco and Fuentes d'Onoro. Later he was a made a Commander of the Order of the Bath. When returning to England from Ostend, his ship sank in the harbour and Napier narrowly escaped. He devoted the next two years to studying military and political history, agriculture, construction and political economy.

In 1819 he was sent to the Ionian Islands. At this period much of Greece was under the Ottoman Empire. Napier had the position of resident in Cephalonia, an office created by the high commissioner and in this role he was active in the field of public works and road building. He was also involved in military advice to the Greek government and the Greek committee in London and was interested in supporting their cause against the Turks. In 1825 he was promoted to full colonel. He returned to England for a time when his mother died in 1826 and in April of 1827 he married. Napier and his wife went to Cephalonia until 1830, but returned because of her health. In 1833 he was affected by the cholera epidemic and later that year his wife died. He moved then to Caen in Normandy and concentrated on the education of his daughters. In 1835 he married for a second time and settled in Bath. He had already written a book on his government of Cephalonia but now he wrote a dialogue on the Poor Laws, a book on military law and edited a book Lights and Shadows of Military Life, from the French of Count Alfred de Vigny and Elzèar Blase. In addition he wrote a historical romance which was never published.

In January 1837 he was promoted to the rank of major general and early the following year moved to Milford Haven. In July 1838 he was made KCB. His next major appointment was to the command of the eleven counties of the Northern District of England at a time of civil unrest caused by the Chartists. At the time the Chartists were seen as dangerous revolutionaries by the government and ruling classes but their aims now seem to be justifiable and fair - they wanted universal suffrage, an end to property qualifications to stand for parliament, paid MPs so that ordinary working men could stand. Napier was sympathetic to these political views but had the task of maintaining order at a time when there was no police force and the magistrates had to call on the military in the event of serious disturbances. He was appalled at the squalor of Manchester and described it as "the chimney of the world" and as "the mouth of hell." In relation to the slow progress of reforms to help working families he said "famished men can't wait." (These quotations are in Victorious Century by Professor David Cannadine, published by Allen Lane, 2017, ISBN 0713998148)

In October 1841, Napier sailed for India to take command at Poona. The Governor-general was Lord Ellenborough, who asked Napier to assess the military position. Napier recommended the relief of Jalalabad and a two pronged attack on Kabul from Peshawar and from Kandahar. In September 1842, Napier was given command of the region of Upper and Lower Sind and sailed for Karachi. Shortly after arrival, Napier was wounded in the leg by an explosion. When he recovered he proceeded up the Indus to Hyderabad and Sakhar to take command of the military forces. Here he found a complex political situation with three sets of rulers in Upper Sind, Lower Sind and Mirpur. Britain had a treaty allowing them to be stationed in Shikarpur, Bakhar and Karachi. However, setbacks in what is now Afghanistan had weakened British prestige in the area and the the local rulers were looking for opportunities to exploit the situation. Local leaders complained of tolls being levied by the British and it was then discovered that there were secret talks with adjacent tribes to attack British forces.

Napier moved to Shikarpur and on 15 December British troops moved to occupy Rohri. At the turn of the year he decided to seize the fortress of the amirs at Imamghar, which lay in desert country east of Sind. Troops travelled by camel and horse but when they arrived on 12 January the fortress had been evacuated. Napier rested his men for three days then blew up the fortress and headed for Pir Abu Bakar on the Indus. This was a point where he could threaten both Hyderabad and Khairpur. Napier had authority from the Governor-general to force a new treaty on the amirs of both provinces. Attempts at negotiations were made in January but Napier sent Captain James Outram (later General Sir James Outram) , the chief political officer of the area, to Hyderabad while he moved south to Nowshera. Outram believed a peaceful outcome was possible but Napier received reports of a force of 25,000 men gathered near Hyderabad, 10,000 Khandesh tribesmen were moving along the left bank of the Indus, a further 7,000 were near Khunhera and 10,000 under Shir Muhammed were advancing from Mirpur. Outram met the local leaders on 12 February 1843 and all signed a new treaty except one. However, the situation on the streets deteriorated rapidly and the residency was attacked on 15 February. Outram was forced to fight his way back to the river to rejoin the transport boats to enable him to rejoin the army.

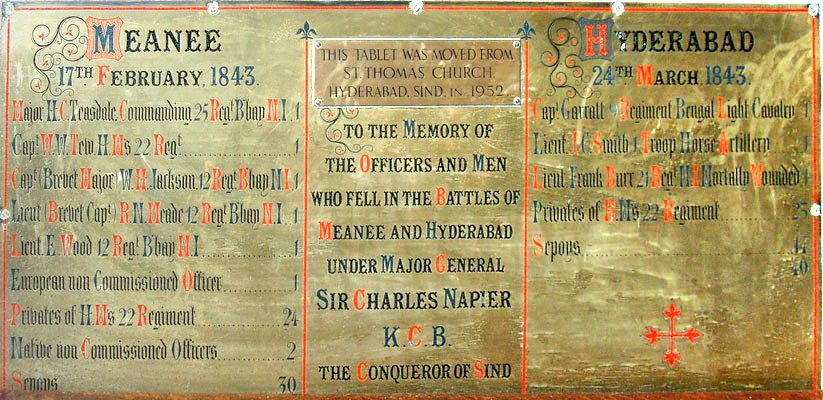

On 6 February, Napier moved towards Sakarand, arriving on the 11th and then on to Sindabad and by the 16th reached Matari. An enemy force of 22,000 was then about ten miles from him near Meanee. Napier had 2,800 men. Of these, 400 were in charge of baggage and 200 were sent to Outram to set fire to forests on the enemy flank. Of the 2,200 remaining about 500 were European. The two forces met at about 9 o'clock on the morning of 17 February. Napier drew up all the baggage train and animals in the rear and set up firing positions for the armed camp followers together with the support of 250 members of the Poona Horse and four companies of artillery. On his right he drew up his artillery of 12 guns followed by the 22nd Queen's Regiment and on his left were the 25th, 12th and 1st native regiments. These were drawn up not in line but in echelon to allow for manoeuvre. On the left flank were the 9th Bengal Cavalry and the Sind Horse. The amirs had placed their forces on the outside of a bend in the river Falaili and a stone wall enclosing a wooded area hid about 6,000 Baluchis. The amirs forces had 18 guns.

Napier moved forward and seeing an opening in the wall on his right he sent Captain Tew with a company from the 22nd Queen's Regiment block it and thus prevent the egress of the Baluchis. Tew was killed but the force of 80 men held the breach in the wall. The main British force advanced under heavy fire, and then charged up toward the bank of the river Falaili only to discover that there were thousands of enemy troops in the dried up river bed beyond. The troops were then occupied for about two hours near the brink of the bank. They went forward to fire into the enemy in the river bed and returned to reload. The Baluchis made several charges but were pushed back and when the British guns blasted holes in their line it was continually replenished from behind. At length Napier ordered the cavalry on his left to advance against the enemy's right. They charged through the enemy guns, over the bank of the river and behind the main enemy force As the Baluchis turned to witness the threat, the British infantry charged pushing them backwards and there was hand to hand fighting but the battle was won. The British forces lost 20 officers and 250 men and the Baluchis had 6,000 killed or wounded. Hyderabad surrendered.

During the course of this battle, Napier, who was by now 60, had a narrow escape. One of the Baluchi chiefs marked him out for attack and approached with sword and shield. Napier had damaged his right hand and shifting his reins to his injured hand he prepared to defend himself with his sword. He was about to engage the enemy when Lieutenant Marston sprang forward to intervene. A fierce fight ensured in the midst of the smoke and dust and just when the Baluchi chief seemed about to deliver a fatal blow, he received a bayonet in his exposed side. Napier was unable to find out which soldier was responsible for saving the situation.

Shir Muhammed of Mirpur was not involved in the battle but was a few miles away with a further 10,000 men. He returned to Mirpur and gathered a force of totalling 25,000. Napier now facing intense heat had to garrison Hyderabad with 500 men. He called for reinforcements along the Indus from Sakhar and these included regiments of Bengal Cavalry, native infantry and horse artillery. Major Slack with a brigade of 1500 and five guns moved south to join Napier on 22 March. Napier made a fortification near the Indus and secured the defence of his river steamers. On 23 March the reinforcements from Sakhar and Bombay arrived. Shir Muhammed called on Napier to surrender but on the 24th Napier answered with an attack on Dubba, 8 miles from Hyderabad, where Shir Muhammed had 26,000 men and 15 guns with their right defended by a river and a line of infantry stretching two miles to a wood. The cavalry was on the left away from the river.

Napier had 5000 men, of which 1100 were cavalry. He had a total of 19 guns with five from the horse artillery. He attacked along the line of the river with the horse artillery supported by two regiments of cavalry. The infantry line was made up of the 22nd Queens and four native regiments and on the right the 3rd cavalry and Sind horse. The enemy front line was attacked from the side by the horse artillery but when the British infantry moved forward they discovered a second entrenched line of enemy. After a hard battle, in which Napier led the charge the field was his. Napier lost 270 men and 5000 of the enemy were killed. Napier himself had a narrow escape when an enemy magazine blew up killing several people around him. Napier set off to Mirpu in pursuit of Shir Muhammed only to find that he had fled to Omerkot. On 4 April the Sind horse and camel battery reached Omerkot, but their quarry had fled. On 14 June Major John Jacob caught up with Shir Muhammed again and defeated him, forcing his escape across the Indus.

The story developed that on conquering Sind, Napier sent the one word message of "peccavi" back to headquarters, which is the Latin for "I have sinned". According to one report, a young woman sent a letter to Punch magazine suggesting that General Napier might have used the pun. The editor liked the idea and ran the story as if Napier had sent the message to the War Office. It then passed into general circulation.

Thus, Sind was annexed to British India - a controversial move at the time as some had believed that a negotiated settlement might be possible in which Britain controlled the area through its local rulers rather than by defeating them. Napier became governor of Sind and was able to exercise the interest and skill in administration that he had shown in Greece. He received the submission of local chiefs and set about organising a police force, courts and civil administration. He promoted the idea of developing Karachi as a major port. One of the novel features that Napier introduced into his despatches was the mention of private soldiers for acts of gallantry. His interest in the welfare of his men, both British and native regiments, made him popular with the troops. On 24 May 1844 he organised a durbar at Hyderabad, attended by 3000 Sindian Baluchi chiefs and 20,000 men to celebrate Queen Victoria's birthday. Napier was made a G.C.B., and on 21 November 1843 was given the colonelcy of the 22nd regiment. His military achievements at what became known as the battles of Meanee and Hyderabad, his gift for civil administration and his writing were all highly commended by the Duke of Wellington and by Robert Peel, the Prime Minister.

In late 1844, Napier moved against the tribesmen under Beja Khan Dumki, who had been raiding Sind from the north. Sakhar became his base just before Christmas but there was an outbreak of disease that killed many of the 78th highlanders. The tribesmen expected this to delay Napier but he advanced with forced marches to surprise them and captured thousands of cattle, and much grain, forcing the enemy into the hills. He then waited at the passes for his guns to arrive and advanced in January. He captured Pulaji, Shahpur and Ooch and drove Beja Khan to take refuge at Traki, a rocky outcrop with vertical sides 600 feet high and only two openings. However, Napier captured Beja Khan on 9 March and then returned to Sind.

On 13 December 1845, the first Sikh war began. By 6 February Napier assembled a force of 15,000 men and 86 guns at Rohri. The battle of Ferzeshah was fought during February and the Governor-general, Hardinge, who had replaced Lord Ellenborough, ordered Napier to move his forces on Bhawalpur and to come in person to his headquarters in Lahore. He reached there on 3 March to find that a battle had been fought at Sobraon and the war was over. He returned to Karachi where an outbreak of cholera killed 7000. Among the casualties were 800 soldiers including Napiers nephew John Napier. On 9 November 1846 Napier was promoted to Lieutenant-General. The following October he returned to Europe.

Napier lived in Cheltenham and occupied himself writing pamphlets on administration in the Indian Army. However, by 1849 there were further problems in India and the East India Company asked the Duke of Wellington to recommend a general to take command. Wellington put forward Napier as his nomination but it was rejected and instead Sir William Maynard Gomm was despatched from Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. By the end of February there was news of the battle of Chillianwallah and there was agitation for Charles Napier to be sent. He reached Calcutta on 6 May to assume command but by then the war was over and Napier gave due credit to Lord Gough for the successful conclusion.

Napier had agreed to go as General only if given a seat on the governing body of the East India company but in due course he was in disagreement with the Governor-general Lord Dalhousie over a contentious issue relating to service conditions for the native soldiers. Napier resigned and left Simla on 16 November 1850 reaching England in March 1851. He had been suffering from a serious liver condition since 1846 but was a pall-bearer at the funeral of the Duke of Wellington at St. Paul's Cathedral on 18 November 1852. Napier died at Oatlands on the morning of 29 August 1853, with the colours of the 22nd regiment borne at Meanee hung above his bed. He was buried at the Garrison Chapel at Portsmouth. Some 60,000 people turned out for the occasion. The pictures below show the Chapel, which was damaged by bombing in World War II. The monument lies in the churchyard in front of the ruined nave. The brass plaque is displayed in the choir of the church. The pictures below were taken in May 2010.

|

|

|

| Garrison Church | Tomb | |

|

|

|

| Arcade of ruined nave | Plaque displayed in the choir |

This article is condensed from a fuller account to be found in an article formerly on the web by Marjie Bloy, which is itself taken from Sir Lesley Stephen & Sir Sidney Lee

(eds.), Dictionary of National Biography from the earliest times to 1900

(London, Oxford University Press, 1949). It mentions that there is a bronze

statue of Napier on a granite base about 100 metres from the Athenaeum in Pall

Mall as well as the statue in Trafalgar Square.

General Sir Charles James Napier, GCB, 1781-1853, an eight-page pamphlet by Emeritus Professor A. J. Pointon of the University of Portsmouth can be purchased at the Garrison Church

Heroes of England by J. G. Edgar, Everyman Series, published by J. M. Dent and Sons, London has a fourteen page article on Sir Charles James Napier. This book was first produced in 1858 and is described as "biography for young people". It gives a very glowing and patriotic account of figures from the Black Prince to Sir Henry Havelock. It includes a few details on Napier not found in the DNB article.